Understanding the Impact of Father-separation on Well-being in Forcibly Displaced Syrian Children

Authors

Annisha Attanayake, Michael Pluess, and Hend Eltanamly.

Key Messages

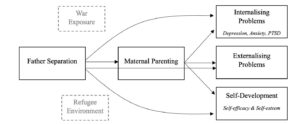

Forced displacement uproots children from their homelands, stripping them of basic needs like stability, education, security, and their social networks. Some children even have to grow up separated from their fathers who might be detained by fighting forces, dead, or went to seek safety for the family elsewhere. The consequences of such separation on children’s well-being can be drastic, but is often researched in families with an incarcerated father. Not much is known about the impact of father separation in the aftermath of war exposure. This study sought to understand how father separation impacts Syrian refugee children’s mental well-being. Researchers also examined whether father separation was related to worse maternal parenting, explaining any adverse effects on children’s well-being. Researchers looked at different aspects of well-being, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; internalising problems), aggression (i.e., externalising problems), and self-development (i.e., self-efficacy and self-esteem).

Background

War can cause families to be forcibly separated, and children bear the heaviest burden

War and forced displacement tear families apart, often leaving children to grow up without their fathers. But how does this separation affect their emotional well-being and development? To truly understand the impact, we need to compare refugee children who are separated from their fathers to those who still have them present.

Of course, we can’t—and shouldn’t—experimentally separate families for research. However, among the millions of forcibly displaced families, some children experience father separation due to circumstances beyond their control—whether their fathers have been detained by fighting forces, killed, or have left to seek safety for the family elsewhere. This creates a natural opportunity to study the effects of father absence in real-world conditions.

In our study, we examined 1,600 Syrian refugee children living in informal settlements in Lebanon, 367 of whom were separated from their fathers. We aimed to answer four key questions.

What were the aims of this study?

Investigating the effects of father separation on child mental health

- Who are the children most affected? The researchers explored demographic differences and the reasons behind father separations.

- How does father separation affect children’s well-being? The researchers looked at symptoms like anxiety, depression (internalising problems), and behavioural challenges (externalising problems), as well as self-development.

- What other factors shape children’s well-being? The researchers also examined how war exposure, living conditions as refugees, and parenting practices differ between children with and without their fathers.

- Does a mother’s parenting make a difference? And finally they investigated whether maternal parenting, as reported by the children themselves, helps buffer the negative effects of father separation.

Figure 1. The impact of father separation on forcibly displaced children whilst controlling for levels of war exposure and refugee environment.

How was this study carried out?

Over 1,500 displaced children living with their mother were interviewed.

The study included 1,544 Syrian refugee children (aged 8–17) residing in informal tented settlements in Lebanon, 367 of whom were separated from their fathers. Researchers assessed children’s war exposure (WEQ), refugee living conditions, maternal parenting quality – as reported by the children, and different well-being measures. This was done iin interviews conducted with both the child and their caregiver which lasted for around 50–60-minutes. Validated psychological scales were used to measure depression (CES-DC), anxiety (SCARED), post-traumatic stress disorder (CPSS), and self-efficacy [1].

What were the key findings?

Father separation is linked to depression, lower self-esteem, and diminished self-efficacy.

The study revealed a harsh reality: refugee children separated from their fathers not only endured more war-related trauma but also grew up in worse living conditions than those who still had their fathers present. The impact on their mental health was profound—these children showed significantly higher levels of depression and PTSD, underscoring the deep emotional strain of losing paternal support.

Beyond mental health, their self-efficacy—the belief in their ability to shape their own future—was notably lower, reflecting the importance of secure attachment in childhood (attachment theory [2]). They also reported lower self-esteem, suggesting a diminished sense of self-worth.The researchers, however, found no significant differences between father-separated and non-separated children when it came to anxiety or externalising behaviours like aggression. This challenges some assumptions about how father absence affects emotional regulation.

Also contrary to their expectations, maternal parenting did not explain these effects on children. While factors like maternal acceptance, psychological control, and neglect were strong predictors of overall child well-being, they did not explain the specific impact of father separation. This suggests that while a mother’s role remains vital, losing a father has a unique and independent effect on a child’s mental health and development.

These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted support for father-separated refugee children, addressing both their emotional struggles and the challenging environments they live in.

What are the implications of this research?

As a significant stressor, father separation must be recognised in the refugee crisis.

The findings from this study make one thing clear: refugee children separated from their fathers need targeted mental health support to address depression, low self-esteem, and a diminished sense of efficacy. Strengthening maternal support is also crucial, as single refugee mothers often face overwhelming psychological and financial stress. Providing them with both emotional and economic assistance could improve their children’s well-being.

Beyond mental health, education and empowerment programs should be prioritized. Safe spaces for learning and play can help children build resilience, develop autonomy, and regain a sense of normalcy. Structured activities may help mitigate the negative effects of father separation and foster positive self-development. More research is needed to understand the long-term impact of father separation. Does reunification, if it happens, help children heal, or does it bring new challenges with it? Understanding these dynamics is essential for shaping effective interventions.

This study underscores the need to recognise father separation as a major stressor in the refugee crisis. Addressing it through policy and targeted interventions can help displaced children regain a sense of security, stability, and belonging – key ingredients for a healthier future.

About the study team

This study was carried out by a team of experts in psychology, including Hend Eltanamly from Utrecht University, the Netherlands; Andrew May and Michael Pluess from University of Surrey and Queen Mary University; Fiona McEwen from Queen Mary University and Kings College London and E. Karam from IDRAAC, Lebanon.

References

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalised Self-Efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). NFER-NELSON.

- Bowlby, J. 1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 145 (1), 1-10.

- Eltanamly, H., May, A., McEwen, F., Karam, E., & Pluess, M. (2024). Father-separation and well-being in forcibly displaced Syrian children. Attachment & Human Development, 1–21.