Supporting the Mental Health of Forcibly Displaced Children: A Call to Action

Authors

Annisha Attanayake, Michael Pluess, Felicity L. Brown and Catherine Panter-Brick.

Key Messages

In the face of escalating global conflicts, natural disasters, and political instability, the number of forcibly displaced individuals worldwide has surged, with children making up nearly half of the displaced population. Among this vulnerable group, the psychological toll of displacement can be immense and long-lasting. This review paper presents a comprehensive and urgent appeal for stronger, evidence-based efforts to support the mental health of forcibly displaced children.

Understanding the Scope of the Crisis

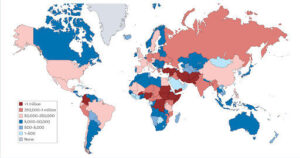

By the end of 2023, 47.2 million children (younger than 18 years) were forcibly displaced globally – the highest number since World War II. This includes refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced children, the majority of which resettle in low- and middle-income countries. Many of these children experience post-resettlement challenges (e.g., discrimination, poor living conditions, and limited access to education and healthcare) alongside the long-term effects from having been exposed to a range of adversities, including war, persecution, the trauma of flight and family separation.

According to empirical studies, about 50% of forcibly displaced children experience mental health problems – over 4 times higher than the global estimate (13%) for non-displaced children.

Figure 1. Origin and residence of forcibly displaced children in 2023.

The prevalence of mental health conditions across studies tend to vary due to differences in age, country of origin, and pre- and post-migration experiences. Seven systematic reviews consistently show that forcibly displaced children experience high rates of mental health conditions, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. However, most research focuses on displaced children that resettled in high-income countries (HICs), neglecting children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) who often face greater risks. Contextual factors like living conditions (e.g., informal settlements vs. urban housing) further influence mental health outcomes but are not yet well understood.

Risk and Resilience: A Balancing Act

A key insight from the review paper is that while displacement presents a serious risk to mental health, outcomes vary greatly depending on a host of risk and protective factors. On one side of the equation are risk factors which increase the vulnerability for the development of mental health problems, including:

- Exposure to traumatic events (e.g., violence, death, or torture)

- Chronic stressors in host countries (e.g., racism, poverty, insecurity)

- Family separation or parental distress

- Legal uncertainty regarding asylum status

On the other side are protective factors which promote resilience in forcibly displaced children and reduce the risk for mental health problems. Such protective factors include:

- Supportive relationships with caregivers or peers

- Access to education and mental health services

- Stable living conditions

- Opportunities for social integration and participation

Risk factors and protective factors along with individual differences in children’s sensitivity to environmental influences interact to shape the developmental trajectories of displaced children. However, more research is required to better understand the interplay between the different factors regarding risk and resilience.

Mental Health Interventions: Promising Approaches, Limited Evidence

While attention to mental health interventions for forcibly displaced children is increasing, this review notes that many lack a strong evidence base due to research gaps. Ten systematic reviews reported interventions across various settings, but methodological weaknesses were common, and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials found no clear effects for children specifically.

Research shows that family and school-based interventions hold promise for supporting the mental health of forcibly displaced children, but the evidence is still limited. Family-focused approaches, like parenting support and systemic family therapy, have shown some positive results but most studies are based in high-income countries (HICs), even though the majority of displaced families live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Consequently, there is a lack of research on families facing severe distress and those living in humanitarian settings.

Schools often serve as a key space for delivering mental health support. Some interventions, especially those using cognitive behavioural techniques, creative arts, and trauma processing, have shown benefits. Yet, again, most evidence comes from HICs, and studies in LMICs often face methodological weaknesses.

Community-based approaches are of particular importance. These aim to put local people in charge of designing and delivering interventions, reducing stigma and building collective well-being. However, there’s still very little research on how to effectively involve communities in supporting the mental health of displaced children.

Overall, while there’s growing interest in these types of interventions, more research is needed, especially in low-resource and humanitarian settings, to understand what works, for whom, and in which contexts.

Cultural adaptation of interventions is crucial

Cultural and contextual considerations are essential when delivering mental health and psychosocial support to forcibly displaced communities. While many current interventions are based on Western models, these often do not align with local understandings of psychological distress, potentially reducing effectiveness or causing harm. Research shows that few interventions are culturally adapted, and those that are tend to make only minor adjustments. Effective adaptations balance “fidelity” (maintaining core components) with “fit” (ensuring cultural relevance and acceptability). For example, a psychological intervention for Syrian adolescents displaced to Lebanon involved thorough contextualization through research, community input, and pilot testing to ensure cultural relevance and engagement.

In addition, the review stressed the importance of training local professionals and lay providers to deliver interventions effectively. Capacity building within host communities is essential for creating sustainable systems of care.

From Awareness to Action

This review is not just a call for better research, it is a call for systemic change. Governments, NGOs, and international organizations must collaborate to ensure that mental health care for forcibly displaced children is prioritized and embedded within humanitarian responses.

This includes:

- Allocating dedicated funding for mental health services in refugee settings

- Integrating psychosocial support into education, health, and social care systems

- Ensuring legal protections and stable environments for displaced families

- Promoting social inclusion and countering xenophobia in host communities

The authors highlight that mental health is a fundamental human right. Addressing the psychological needs of displaced children is not only a moral imperative but a sound investment in social cohesion and global stability.

Guidance for future research

This review highlights the complex, diverse factors affecting the mental health of forcibly displaced children, recommending a multisectoral, socio-ecological approach to mental health and psychosocial support services. Despite global frameworks advocating for these approaches, implementation remains limited, and research gaps hinder effective policy and program development.

Key recommendations include conducting longitudinal, mixed-methods studies to better understand the risk and protective factors at different stages of displacement, as well as examining broader psychosocial outcomes beyond traditional mental disorders. There is also a need to address intergenerational mental health dynamics, particularly in family and caregiver contexts.

While interventions targeting individual children have shown some promise, there’s a notable gap in research addressing the broader socio-ecological factors affecting displaced children. This is especially true in humanitarian settings where evidence on effective mental health and psychological support services is scarce.

Taking a shared responsibility

Future efforts should focus on integrating systems thinking into interventions, promoting long-term well-being through community engagement, and enhancing access to education, legal protection, and socio-economic opportunities. Additionally, to overcome resource constraints, there’s a need to train non-specialist workforces and scale up effective, culturally relevant interventions.

Ultimately, a science-driven, comprehensive approach is essential to improving mental health support for displaced children, ensuring equitable access, and fostering sustainable, positive mental health outcomes.

About the Study Group:

This review has been written by Michael Pluess (University of Surrey and Queen Mary University of London), Felicity L. Brown (UNICEF Headquarters, New York), and Catherine Panter-Brick (Jackson School of Global Affairs and Department of Anthropology, Yale University).

References

Pluess, M., Brown, F. L., & Panter-Brick, C. (2025). Supporting the mental health of forcibly displaced children. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1-18.